We continue straight on from Part 1, and what follows is going to be more historical than my usual spiritual and philosophical ramblings. But don’t worry, I will be making up for that in the following parts. I’m sorry to disappoint - or perhaps you’ll be relieved to know - that I will not be diving into the details of the Jack the Ripper murders themselves. Instead, my focus here is on the impact those crimes had on the society of that time and, more importantly, what they revealed about the state of the city and the lives of its inhabitants. The murders were horrific, no doubt, but what they revealed was something maybe even worse.

The 1800s were a time of rapid growth and change for London. It was the largest city in the world, and as the capital of the British Empire, London was a global hub of trade, finance, and industry, attracting millions of new citizens. The city started the century with a population of around a million, and by the time the 1900s came around, that number had swelled to over 6 million inhabitants, with the city itself sprawling out to include more suburbs. It’s easy to mention numbers like that, but what do they actually mean? They mean that people were pouring into the city, all needing places to live, ways to earn an income, and access to basic necessities like food, healthcare, and education. But what really helped me grasp the enormity of this population boom was when I fell in love with Brompton Cemetery in West London. I lived nearby and walked there often. This cemetery is one of seven collectively known as ‘The Magnificent Seven’; they were all opened between 1833 and 1841. The increase in population meant that the local parish churches, which typically handled burials, were overwhelmed. There was literally nowhere to put London’s dead, and piling bodies on top of each other was regarded as a disrespectful way to treat the deceased. Even more than offending people’s sensibilities, the sheer number of bodies was causing disease and sickness.

Even though he was not writing about London, the opening paragraph of Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities very much sums up life in London at that time:

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way…”

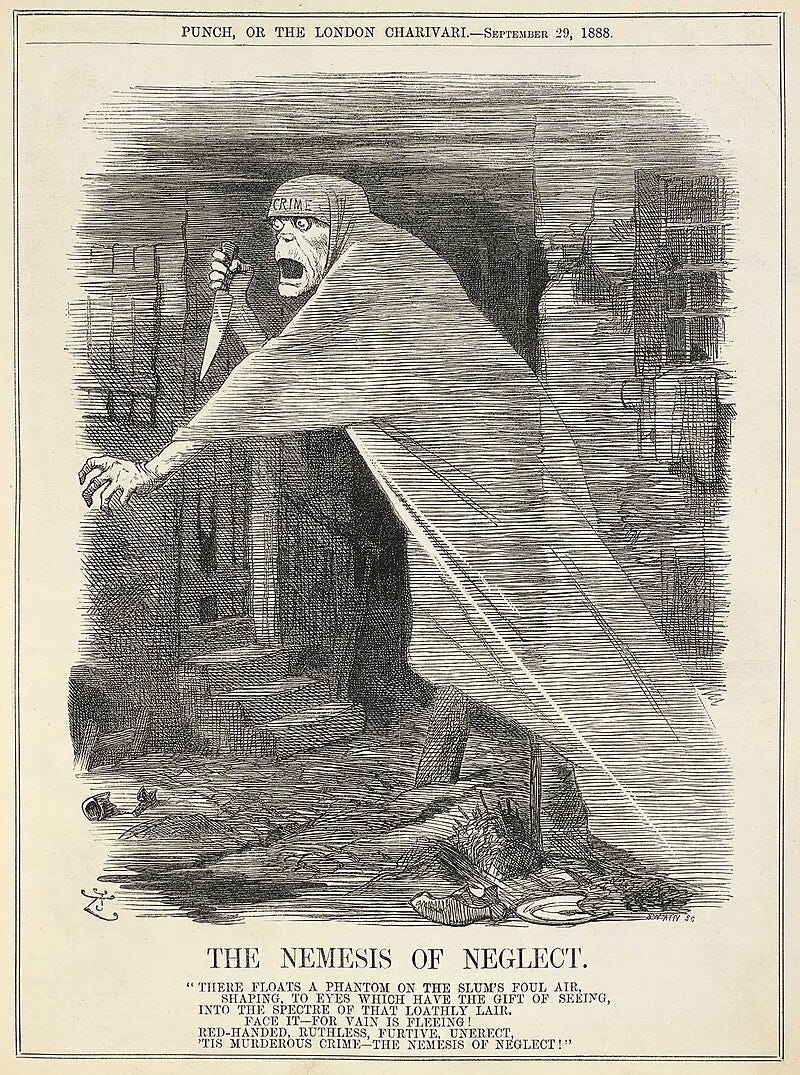

Yes, there was much wealth in London, and this was reflected in its technological advancements like the railways and electric lighting, which were transforming daily life. But the city’s rapid expansion brought severe overcrowding, especially in the East End, where poverty, crime, and poor living conditions were rampant. While the affluent West End flourished with its grand boulevards, theatres, and shops catering to the upper class, the East End became infamous for its squalor and lawlessness. The West Enders often viewed the East End with a mix of pity, fear, and disdain, seeing it as a breeding ground for crime and vice, populated by those they considered the "undesirable" elements of society.

The stark contrast between these two worlds was evident not only in the quality of housing and public amenities but also in the job opportunities available. In the East End, many residents were forced to take up insecure, poorly paid work, such as casual labour on the docks, in sweatshops, or, in the case of many women, tailoring clothes. These jobs offered little stability and even less hope for upward mobility. Some of the prostitutes plying their trade in East London had previously held ‘respectable’ jobs, but all it took was for the loss of a partner or job and they had no other options. Meanwhile, in the West End, jobs were more stable and better paid, with many employed in professions, trade, or the arts. This economic divide was mirrored by a cultural one, with the West End viewing itself as the heart of civilised London, while the East End was often "othered" as a dangerous, foreign part of the city.

The Metropolitan Police, still finding its footing, struggled to maintain order in this complex and divided city. In 1888, the sensational Jack the Ripper murders of prostitutes in Whitechapel exposed the harsh realities of life in these slums, drawing public attention not just to the crimes themselves but to the conditions that allowed such horrors to occur. The West End's reaction to these events was telling: rather than addressing the systemic issues of poverty and inequality, the focus often shifted to charity drives or minor reforms, with the media playing a significant role in shaping public perception and discourse.

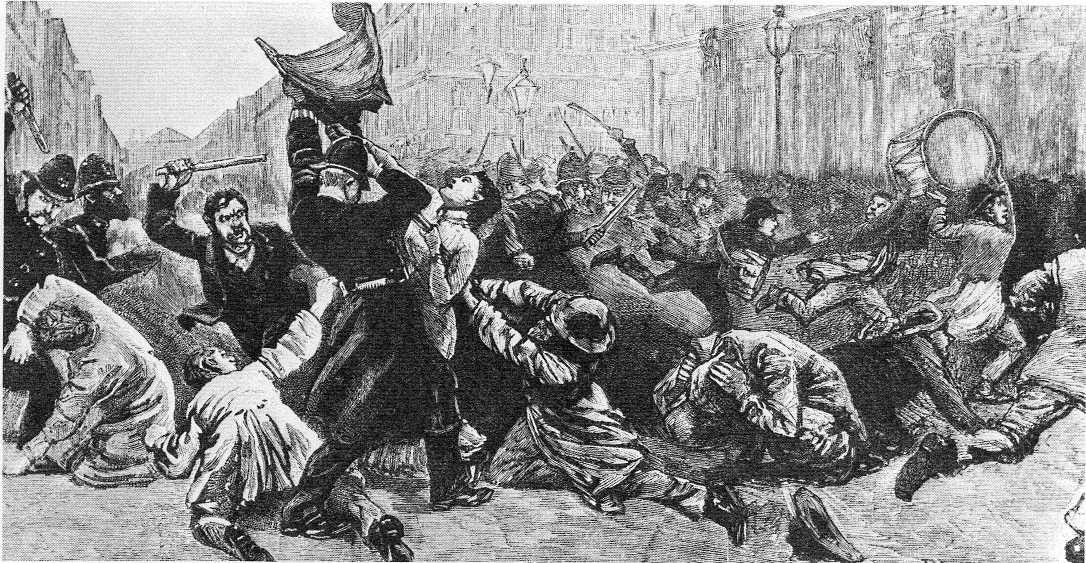

It wasn’t just about the overcrowded slums, though. London in the late 19th century was a boiling pot of social unrest. Just a year before the Ripper murders, on 13 November 1887, the city witnessed ‘Bloody Sunday.’ This was a protest held in London, specifically in Trafalgar Square, a central location for public demonstrations at the time. The protest was primarily against the British government's coercive policies in Ireland, with underlying issues of unemployment and poor working conditions also contributing to the discontent. It ended in a violent clash between demonstrators and the police. The protest was led by socialists, and the response was brutal; hundreds were injured, and several people were reportedly killed. This wasn’t just about a protest gone wrong - it was a clear indication of how the working class's freedom of expression was being crushed. The government, led by the Conservative Party under Lord Salisbury, used the police to do its bidding, ensuring that dissent was met with force. The events of Bloody Sunday underscored the growing tensions between the working class and the establishment, tensions that would continue to simmer beneath the surface, only to explode in various forms throughout the years to come. The incident was a stark reminder of the inequalities and injustices faced by many, and the increasingly heavy-handed approach the authorities were willing to take to maintain order and quash dissent.

The Ripper murders, occurring less than a year later, did not happen in isolation but against this backdrop of social turmoil. They became a symbol of the fear and unease that was already gripping the city. It is often said that Jack the Ripper is the first serial killer, but murder was not new to London, nor was the press. What changed and gave Jack the Ripper the notoriety and staying power - where I can still talk about the Whitechapel murders today and be pretty certain that most people will be aware of what I am referring to - is the crucial role played by the tabloid press in the Ripper case, sensationalising the crimes and amplifying public fear. Take the name ‘Jack the Ripper,’ for example. In all police files and journalistic reports from that period, the killer is referred to as ‘The Whitechapel Murderer’ and ‘Leather Apron.’ The name ‘Jack the Ripper’ originated from the infamous ‘Dear Boss’ letter, which was likely a hoax written by journalists to boost newspaper sales. Media coverage, including the ‘From Hell’ letter sent to George Lusk (the chairman of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee) with half a human kidney, fuelled public belief in a single, brutal serial killer, cementing Jack the Ripper's infamous legacy.

Beyond the sensationalism of the press, the Victorian era's fascination with spiritualism also played a role in the case. The police received numerous letters from spiritualists from across the country, who claimed to have gained insights into the identity of the murderer through séances and table-tapping. These letters, often vague and contradictory, added to the confusion and misinformation surrounding the case, further complicating the already difficult task of the police. Spiritualism was a significant cultural movement during this period, and its influence on the public's perception of the murders is another example of how the Ripper case became intertwined with the broader social currents of the time.

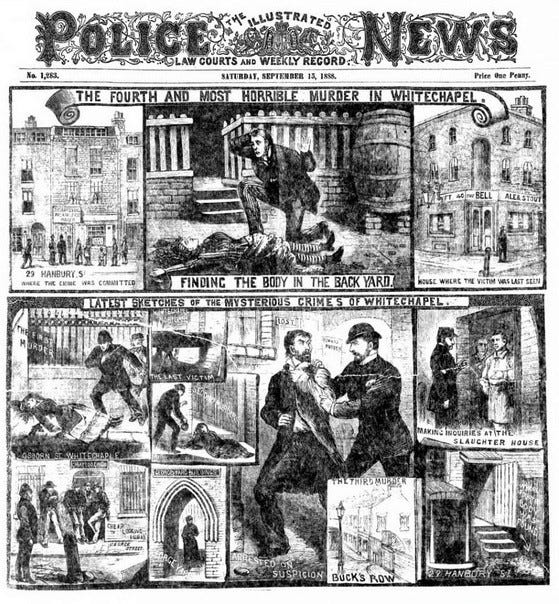

Due to reporters looking to boost readership, there was much interference with what was already rudimentary police investigating, and there is still debate over the actual victims of the murderer. From the period of 3 April 1888 to 13 February 1891, there were 11 murders included as ‘the Whitechapel Murders,’ but the 5 most widely accepted as having been committed by Jack the Ripper are from 31 August to 9 November 1888. These murders were not just reported nationally either; there was press coverage about the murders in the US, Australia, and other countries, making them a global sensation and revealing the dark underbelly of London to the world.

Whitechapel was a melting pot of cultures in the late 19th century, exacerbating the xenophobic attitudes of the time. Irish immigrants, who had been arriving since the 1840s, were fleeing the devastation of the Great Famine, a catastrophe exacerbated by British policies that left millions starving and destitute. These immigrants were often met with hostility due to stereotypes of drunkenness and violence, further fuelled by the actions of the Fenian nationalist group, which aimed to establish an independent Irish Republic through armed rebellion against British rule. The 1880s brought a significant influx of Eastern European Jews, many of whom were escaping pogroms and persecution in the Russian Empire. They faced intense prejudice in London for their perceived unwillingness to integrate, their success in running sweatshops, and their alleged ties to radical political movements like socialism and anarchism. ‘The Illustrated Police News’ capitalised on these fears, particularly during the Jack the Ripper murders, by focusing public suspicion on immigrant communities, illustrating the deep-seated xenophobia that shaped both public perception and police investigations in Victorian London. The paper gained notoriety for its sensationalist reporting, especially during the murders of 1888, combining vivid illustrations with lurid tales. It also published numerous articles on the "alien immigration question," which fostered xenophobic attitudes and heightened paranoia among its predominantly working-class readership. (Due to its graphic content, it was banned in Ireland in 1926 and eventually ceased publication in 1938.)

Before we leave our sojourn in Victorian London, I want to share the front page of ‘The Star‘ from 24 September 1888. The Star was an evening newspaper that had just started publishing earlier that year. (It is also suspected that a couple of the more infamous Jack the Ripper letters were written by reporters working for ‘The Star‘.) Newspapers like ‘The Star‘ were the social media platforms of their time—a space where opinions could be aired, debates ignited, and public sentiment swayed. It’s not a stretch to say that expression back then was limited to those educated enough to write to a newspaper, making the ability to publicly voice one's thoughts a privilege not available to all. These letters, therefore, were both powerful and exclusive.

I know these pieces are quite lengthy, but they offer a window into how people used the media to shape public discourse in much the same way we use digital platforms today. First, is the editorial response to a letter, followed by the letter itself, written by George Bernard Shaw—who we know today as a playwright, regarded by many as being second only to Shakespeare, and his use of satire is evident here.

WHAT WE THINK.

AT the recent meeting of the British Association the dovecots were much fluttered by the appearance of a strange and rather startling figure. A tall, thin man, with a very pale and very gentle face, read a paper which calmly denounced as robbers some of the men the world is accustomed to regard as the ornaments of society, the patterns of morality, and the pillars of the church. This was Mr. GEORGE BERNARD SHAW. The whole thing was done, not with the savagery of a wild and illiterate controversialist, but with the light touch, the deadly playfulness, and the rapier thrusts of a cultivated and thoughtful man. Mr. SHAW is as yet little known to the general world, but he is a power, as he deserves to be, among the militant Radicals of the metropolis. He represents one of the wings - he himself would call it the moderate and rational wing - of the Socialist party. To the propagation of his ideas, he gives up willing time, labor, the opportunities of self-advancement. To such men we can forgive much; their enthusiasm, and their self-devotion are more important than their opinions.

We publish a letter to-day from Mr. SHAW. It is on the hideous and squalid tragedies which, occurring in the East, have stirred up the West-end to unusual and unaccustomed interest in the fate of the poor and the disinherited of the nation. Mr. SHAW writes with what will be considered violence by many, if not by most of our readers, and his proposals are far in advance of those which even some of our most advanced Radicals will be disposed to adopt. They are certainly in advance of any measures that we ourselves are ready to recommend. But we willingly give Mr. SHAW the opportunity of ventilating his ideas; first, because we are in favor of free discussion; and secondly, because though we may not accept his remedies, we sympathise largely with the protest he makes against the fashion in which some of our contemporaries have treated the Whitechapel murders. His revolt against the gush and the cant which are now appearing in certain aristocratic journals, is timely and called for. These journals, which are now calling upon the West to do its duty to the East, are the very journals, as Mr. SHAW points out, which but a few months ago were applauding Sir CHARLES WARREN as warmly and enthusiastically as though he were another Mr. BALFOUR. In the House of Commons, and still more in the drawing-rooms of the West-end, gilded youths and Primrose matrons were pluming their feathers on the spirited way in which the mob had been taught to conduct itself; and after the triumphant reply of Mr. MATTHEWS in the House of Commons, and the splendid majority - largely made up of men calling themselves Liberals - all the reactionaries were congratulating themselves on the excellent results of a policy of coercion in London, as well as in Ireland. On these gratulations come four hideous and squalid tragedies, and at once the same society, that was exultant with class triumph, has grown pale with class terror, and follows with babbling, childish, unctuous proposals - as much a remedy for the state of things revealed as the buns of the French lady for the starvation of the French revolutionaries. We may ask why it required these murders to call attention to the state of the poor at all? The deaths of these unhappy women certainly call aloud for vengeance, and the officials through whose incompetence such things are possible, will be called by-and-bye to a heavy account. But death, sudden, swift, possibly painless - and especially to those who have tried the game of life and have lost honor, self-respect, hope, everything - is infinitely less of a tragedy than the daily struggle for work that can't be got; for food that can't be earned. Give to many of the thousands that stand shivering every morning outside the portals of our great dockyards; give to the man that haunts the coffee shop or the newspaper office every morning to search out the places that are vacant; give to the father of children that meet him at night with the cry for food he hasn't to give - give to many of these the choice between the continuance of life and the painless passage through sleep to death, and the result would be that death would be their choice. It is the tragedy of defeated life, and not the calm of triumphant death, that should appeal to our hearts and imaginations.

And now as to the remedies. First we want better, truer, more honest teaching in our churches. As will be seen from another portion of our impression, a parson is very indignant with us because we have opened our columns to a discussion on the failure of Christianity. The free discussion of any subject is doubtless a soreness and an affliction to many reactionaries - especially when they wear a black coat and have taken service in the Established Church. How can anybody - how can the poor, especially - think well of Christianity when those who are its most eminent - its most highly paid teachers - always take the side which means the further enrichment of the rich, and the deeper impoverishment of the poor? When the landlords had the tax on corn, starvation walked abroad through the land. When reformers like COBDEN and BRIGHT proposed to bring food home to the poor, the clergymen of the Establishment were among the most active apostles of the continued reign of high rates and dear bread, and starved homes. Take the whole talk which is the outcome of these Whitechapel tragedies; does anybody suppose that the interest, shallow and purposeless and resourceless as it is, would have shown itself at all in the days before the people had got some voice in the control of the country? It is the voter and not the man that has excited the interest; and did not, again, the clergymen of the Establishment head the party in town, and still more the country, that opposed by every means in their power the admission of the artisan and the laborer to the franchise? How, we ask again, can we expect humble men to believe in a Christianity which is always on the side of privilege, unjust burdens, deeper poverty, greater helplessness of the weak?

But we can place little confidence in the good teaching of others - or even in their goodwill. The salvation of the disinherited must come largely, if not mainly, through themselves. We have no objection to men like Mr. SHAW preaching their gospel of social regeneration, though we may regard some of their opinions as unwise and impracticable, and the majority of them as unattainable for a considerable time to come. What we ask is that they and their friends shall not neglect the political machinery through which ultimately all changes - social as well as political - have to be attained; and that if they care but little for these things, they will allow others who have taken this work in hand, to go forward without interruption. For our part, we think some of the humblest of these political changes would do much to solve some of the most gigantic of our social problems. Suppose, for instance, that our politicians and our divines, and our social philosophers, and even our Home Secretaries and Police Commissioners, had to deal with a London in which every citizen had a vote - does anybody think that the cry of distress would be drowned in the tumult of bayonets and the clanging of swords? As it is we have to deal in London with masses that are still almost unenfranchised. The vote of London is not a working class, but a middle-class, vote. As long as that state of things lasts, we shall have no proposals for the fundamental changes that will reduce our poverty. We shall have to put up with such canting and shallow philosophy as that which Mr. SHAW so triumphantly assails in our columns to-day.

This is the letter to which the editor responded:

BLOOD MONEY TO WHITECHAPEL.

TO THE EDITOR OF "THE STAR."

SIR, - Will you allow me to make a comment on the success of the Whitechapel murderer in calling attention for a moment to the social question? Less than a year ago the West-end press, headed by the St. James's Gazette, the Times, and the Saturday Review, were literally clamoring for the blood of the people - hounding on Sir Charles Warren to thrash and muzzle the scum who dared to complain that they were starving - heaping insult and reckless calumny on those who interceded for the victims - applauding to the skies the open class bias of those magistrates and judges who zealously did their very worst in the criminal proceedings which followed - behaving, in short as the proprietary class always does behave when the workers throw it into a frenzy of terror by venturing to show their teeth. Quite lost on these journals and their patrons were indignant remonstrances, arguments, speeches, and sacrifices, appeals to history, philosophy, biology, economics, and statistics; references to the reports of inspectors, registrar generals, city missionaries, Parliamentary commissions, and newspapers; collections of evidence by the five senses at every turn; and house-to-house investigations into the condition of the unemployed, all unanswered and unanswerable, and all pointing the same way. The Saturday Review was still frankly for hanging the appellants; and the Times denounced them as "pests of society." This was still the tone of the class Press as lately as the strike of the Bryant and May girls. Now all is changed. Private enterprise has succeeded where Socialism failed. Whilst we conventional Social Democrats were wasting our time on education, agitation, and organisation, some independent genius has taken the matter in hand, and by simply murdering and disembowelling four women, converted the proprietary press to an inept sort of communism. The moral is a pretty one, and the Insurrectionists, the Dynamitards, the Invincibles, and the extreme left of the Anarchist party will not be slow to draw it. "Humanity, political science, economics, and religion," they will say, "are all rot; the one argument that touches your lady and gentleman is the knife." That is so pleasant for the party of Hope and Perseverance in their toughening struggle with the party of Desperation and Death!

However, these things have to be faced. If the line to be taken is that suggested by the converted West-end papers - if the people are still to yield up their wealth to the Clanricarde class, and get what they can back as charity through Lady Bountiful, then the policy for the people is plainly a policy of terror. Every gaol blown up, every window broken, every shop looted, every corpse found disembowelled, means another ten pound note for "ransom." The riots of 1886 brought in £78,000 and a People's Palace; it remains to be seen how much these murders may prove worth to the East-end in panem et circenses. Indeed, if the habits of duchesses only admitted of their being decoyed into Whitechapel back-yards, a single experiment in slaughterhouse anatomy on an aristocratic victim might fetch in a round half million and save the necessity of sacrificing four women of the people. Such is the stark-naked reality of these abominable bastard Utopias of genteel charity in which the poor are first to be robbed and then pauperised by way of compensation, in order that the rich man may combine the idle luxury of the protected thief with the unctuous self-satisfaction of the pious philanthropist.

The proper way to recover the rents of London for the people of London is not by charity, which is one of the worst curses of poverty, but by the municipal rate collector, who will no doubt make it sufficiently clear to the monopolists of ground value that he is not merely taking round the hat, and that the State is ready to enforce his demand, if need be. And the money thus obtained must be used by the municipality as the capital of productive industries for the better employment of the poor. I submit that this is at least a less disgusting and immoral method of relieving the East-end than the gush of bazaars and blood money which has suggested itself from the West-end point of view. - Yours, &c.,

G. BERNARD SHAW

So, that’s it, we’re coming to the end of part 2, and I get it - for a series called ‘A Change of Era,’ I’ve not talked about much change, right? I chose this era to focus on because, yes, it’s far enough in our past to not really have anything to do with any of us, yet I knew how closely the social climate of that time mirrored our own. But even as I was writing this all out, I was hit by waves of incredulity at the similarity between that time and the events and narratives present in the UK and other countries today.

As you were reading, how did this relate to your current reality? Did you see the similarities that I saw? How did you feel about that? If this didn’t resonate with anything going on in your country right now, is it because you avoid any type of news or conversation about current events? What do you focus on instead? Or, if it’s because there is no civil unrest, the media doesn’t have this type of influence, and the people of your country are all equally happy and content, with less authoritarian governments, then please let us know about the paradise you live in, so others can be given hope that these places exist. I’m not joking either - I’ve recently been reading about and listening to José Mujica, and I never thought it would be possible for one old man to symbolise so much hope for me, to be such a beacon of light and the embodiment of another way that I have always believed in, but have seen little evidence of. Yes, I love him, can you tell?

Of course, I should explicitly acknowledge that what I’ve presented here is the barest slice of that era. I picked that time and those events because I know them well, but history is littered with similar times. My intention in highlighting, in the way that I did, these specific aspects is indeed biased; I shared what I did because I wanted to draw parallels between then and now, to show that the patterns we see today have deep historical roots. Recognising these patterns is a start, but the true challenge lies in breaking them, in evolving rather than simply repeating them. That will be the true change of an era. As we reflect on these echoes of the past, we must ask ourselves: if these patterns continue to resurface, what can we do differently to ensure that history doesn't just repeat, but evolves? How do we go from top-down illusions of change to bottom-up actual change? In the next part, we'll explore how these historical patterns intersect with our current reality and what this might mean for us, both collectively and individually - because all is not as it seems.

You know,

I studied some political science at university. To me, the top down illusion happens when citizens fill their heads and attach emotions to governing bodies. If the government isn't pointing weapons at citizens like in a totalitarian regime, then let the government do its thing. Here in the US there's a document on which this country was founded. It makes a lot of common sense.